A team led by Johns Hopkins engineers has discovered some previously unknown properties of a common memory material, paving the way for development of new forms of memory drives, movie discs and computer systems that retain data more quickly, last longer and allow far more capacity than current data storage media.

The research focused on an inexpensive phase-change memory alloy composed of germanium, antimony and tellurium, called GST, for short. The material is already used in rewritable optical media, including CD-RW and DVD-RW discs. But by using diamond-tipped tools to apply pressure to the materials, the Johns Hopkins-led team uncovered new electrical resistance characteristics that could make GST even more useful to the computer and electronics industries.

“This phase-change memory is more stable than the material used in the current flash drives. It works 100 times faster and is rewritable about 100,000 times,” said the study’s lead author, Ming Xu, a doctoral student in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering in Johns Hopkins’ Whiting School of Engineering. “Within about five years, it could also be used to replace hard drives in computers and give them more memory.”

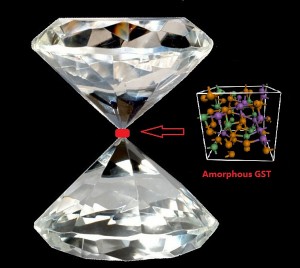

This illustration by Johns Hopkins doctoral student Ming Xu depicts the shape of diamond tips used to apply pressure that uncovered important new properties in the memory medium GST. The inset represents the atomic structure of amorphous GST.

GST is called a phase-change material because, when exposed to heat, areas of GST can change from an amorphous state, in which the atoms lack an ordered arrangement, to a crystalline state, in which the atoms are neatly lined up in a long-range order. In its amorphous state, GST is more resistant to electric current. In its crystalline state, it is less resistant. The two phases also reflect light differently, allowing the surface of a DVD to be read by tiny laser. The two states represent ones and zeros, the language of computers.

Although this phase-change material has been used for at least two decades, the precise mechanics of this switch from one state to another have remained something of a mystery because it happens so quickly—in nanoseconds—when the material is heated.

To solve this mystery, Xu and his team used another method to trigger the change more gradually. The researchers used two diamond tips to compress the material. They employed a process called X-ray diffraction and a computer simulation to document what was happening to the material at the atomic level. The researchers found that they could “tune” the electrical resistivity of the material during the time between its change from amorphous to crystalline form.

“Instead of going from black to white, it’s like finding shades or a shade of gray in between,” said Xu’s doctoral adviser, En Ma, a professor of materialsl science and engineering, and a co-author of the PNAS paper. “By having a wide range of resistance, you can have a lot more control. If you have multiple states, you can store a lot more data.”

Ge-Sb-Te-based phase-change memory is one of the most promising candidates to succeed the current flash memories. The application of phase-change materials for data storage and memory devices takes advantage of the fast phase transition (on the order of nanoseconds) and the large property contrasts (e.g., several orders of magnitude difference in electrical resistivity) between the amorphous and the crystalline states. Despite the importance of Ge-Sb-Te alloys and the intense research they have received, the possible phases in the temperature–pressure diagram, as well as the corresponding structure–property correlations, remain to be systematically explored. In this study, by subjecting the amorphous Ge2Sb2Te5 (a-GST) to hydrostatic-like pressure (P), the thermodynamic variable alternative to temperature, we are able to tune its electrical resistivity by several orders of magnitude, similar to the resistivity contrast corresponding to the usually investigated amorphous-to-crystalline (a-GST to rock-salt GST) transition used in current phase-change memories. In particular, the electrical resistivity drops precipitously in the P = 0 to 8 GPa regime. A prominent structural signature representing the underlying evolution in atomic arrangements and bonding in this pressure regime, as revealed by the ab initio molecular dynamics simulations, is the reduction of low-electron-density regions, which contributes to the narrowing of band gap and delocalization of trapped electrons. At P > 8 GPa, we have observed major changes of the average local structures (bond angle and coordination numbers), gradually transforming the a-GST into a high-density, metallic-like state. This high-pressure glass is characterized by local motifs that bear similarities to the body-centered-cubic GST (bcc-GST) it eventually crystallizes into at 28 GPa, and hence represents a bcc-type polyamorph of a-GST.

If you liked this article, please give it a quick review on ycombinator or StumbleUpon. Thanks

Brian Wang is a Futurist Thought Leader and a popular Science blogger with 1 million readers per month. His blog Nextbigfuture.com is ranked #1 Science News Blog. It covers many disruptive technology and trends including Space, Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Medicine, Anti-aging Biotechnology, and Nanotechnology.

Known for identifying cutting edge technologies, he is currently a Co-Founder of a startup and fundraiser for high potential early-stage companies. He is the Head of Research for Allocations for deep technology investments and an Angel Investor at Space Angels.

A frequent speaker at corporations, he has been a TEDx speaker, a Singularity University speaker and guest at numerous interviews for radio and podcasts. He is open to public speaking and advising engagements.