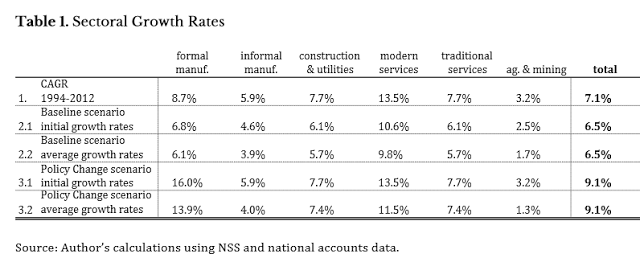

India’s political environment exhibits a new determination to “transform India into a global manufacturing hub,” and in the process raise manufacturing to 25% of GDP and create 100 million new manufacturing jobs. This would entail a structural change comparable to that witnessed by several East Asian countries beginning in the 1960s. The study projects a formal-sector manufacturing boom out 20 years at the sectoral level, assuming India can make the necessary reforms to initiate such a boom. Projection parameters are carefully constructed based on Indian and East Asian historical experience. The projections break out the key growth areas of formal-sector manufacturing and modern services to capture their unique characteristics. The results show large positive gains to aggregate output and employment from initiating an East Asian-style manufacturing boom in India. Reflective of the small size of formal-sector manufacturing employment currently, the government’s specific employment goals appear unattainable in the next 20 years.

Is it realistic that the Indian economy could hit Modi’s goal of creating 100 million new manufacturing jobs by 2022? No

Structural change involves shifting (India’s) economic activity — including its labor force — toward higher-productivity activities,” Green said. “Almost half of India’s labor force works in extremely low-productivity agriculture, and most of the rest works in low-productivity informal activities. The potential for welfare improvements from successful structural change strategies has always been massive, and the political environment exhibits a new determination to take the necessary steps.”

According to Green’s simulation, India’s formal manufacturing sector could grow to attain 27 percent of gross domestic product from the current 11 percent. “Two implications of these results are worth noting,” Green said. “First, the policy-change scenario forecasts that 15 percent of the workforce could be employed in high-productivity industries in the formal manufacturing sectors and modern services. As a comparison point, I have previously estimated that almost half the Indian workforce will have finished high school by 2035, double the share today. This would represent a dramatic improvement over the current workforce.

“The potential rise in education levels above current industry need raises the question of where these workers will find work that will take advantage of their improving education,” Green said. “Another way to look at the potential mismatch is via Say’s Law, which states that supply creates its own demand. It would suggest that businesses that can effectively utilize a better-educated workforce will grow faster on the back of a growing skilled labor supply. Expectations of much better educational attainment would suggest that the projections presented here may be too pessimistic.”

Green did find that Modi’s “Make In India” goals of manufacturing reaching 25 percent of gross domestic product and creating 100 million new jobs by 2022 are worthwhile for inspirational purposes but do not appear to be realistic. “The latter does not even appear realistic in a 20-year time frame,” Green said. “But nobody would be upset about achieving 75 million new manufacturing jobs, which might be realistic with the right basket of reforms.”

The policy change scenario forecasts that 15% of the work force could be employed in high-productivity industries in the formal manufacturing sectors and modern services. As a comparison point, (Green 2014)estimates that almost half the Indian workforce will have finished high school by 2035, double the share today. This would represent a dramatic improvement over the the current workforce. Compare this to the profile of the industries most likely to need workers with at least a high school education. Currently ,48% of workers in organized manufacturing have at least a high school education, 88% of modern service workers and 60% of traditional service workers.

Those sectors employ 29% of workers, and other sectors utilize a much lower share of skilled labor. The potential rise in education levels above current industry need raises the question of where these workers will find work that will take advantage of their superior education. Another way to look at the potential mismatch is via Say’s Law that supply creates its own demand. It would suggest that businesses that can effectively utilize a better-educated workforce will grow faster on the back of a growing skilled labor supply. Expectations of much better educational attainment would suggest that the projections presented here may be too pessimistic.

Second,the main conclusions of this study could be established with a relatively casual parameterization, as the basic results could be attained from a range of realistic assumptions. One point of rigorously parameterizing the model is to rigorously rule out what is not realistic. The Make In India goals of manufacturing reaching 25% of GDP and creating 100 million new jobs by 2022, while worthwhile for inspirational purposes, do not appear realistic. The latter does not even appear realistic in a 20-year time frame. Nonetheless, “big bang” reforms could generate a significant dividend for India under plausible assumptions. This study should provide motivation to the political leadership in state and central governments in India to pursue reforms ambitiously to remove barriers to labor-intensive manufacturing

Brian Wang is a Futurist Thought Leader and a popular Science blogger with 1 million readers per month. His blog Nextbigfuture.com is ranked #1 Science News Blog. It covers many disruptive technology and trends including Space, Robotics, Artificial Intelligence, Medicine, Anti-aging Biotechnology, and Nanotechnology.

Known for identifying cutting edge technologies, he is currently a Co-Founder of a startup and fundraiser for high potential early-stage companies. He is the Head of Research for Allocations for deep technology investments and an Angel Investor at Space Angels.

A frequent speaker at corporations, he has been a TEDx speaker, a Singularity University speaker and guest at numerous interviews for radio and podcasts. He is open to public speaking and advising engagements.